17-year-old Saanvi explores the benefits – and drawbacks – of digitalised medicine

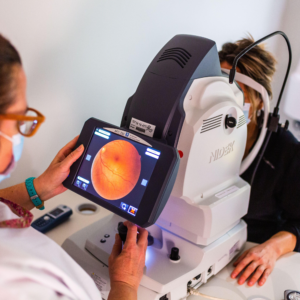

Retinal scans are crucial for early detection of eye diseases.

16 January 2026

Digital symbiosis: Living with the machine

Saanvi Akula was commended in the Harbinger Prize 2025. This is her entry.

From the moment of waking, there is an instinctual urge to reach out for a device, a response that seemingly feels as if it has been programmed into our systems. One would assume that for a generation raised on screens, sensors and seamless connectivity, there would be nothing that could faze us, but the impact of digital technology has penetrated our very biological rhythms.

The young generations of today are growing into an era where a watch notices an irregular heartbeat before we do. Digitalised medicine is currently growing exponentially and, as with every revolution, it brings both extraordinary promise and profound challenges.

For centuries, medical revolutions have centred around the introduction of new tools: the microscope, the X-ray, the MRI scanner… now, AI is evolving to become medicine’s instrument of precision. Neural networks, trained on vast datasets of medical images and gene sequences, are now detecting subtleties invisible to humans.

In 2018, Google’s DeepMind developedan AI system that could accurately detect from retinal scans more than 50 eye diseases, including diabetic retinopathyand macular degeneration.

A 2019 cardiology studyfrom Mayo Clinic showed that AI applied to a standard electrocardiogram (ECG – a test that measures the heart’s electrical activity) could predict the presence of asymptomatic ventricular dysfunction – which increases the risk of a heart attack – with an accuracy greater than 85%.

With such accuracy, it’s not surprising that technology is cementing its place in our lives.

Yet dependence on technology has its own pitfalls. Unlike older generations, who might have waited days (or weeks) for a medical appointment in order to get a diagnosis, we can search symptoms immediately online or via social media. One could argue that this democratisation of information helps us stay informed and gives us more autonomy in navigating the way we access healthcare.

But the same technology that promises life-saving insights can also overwhelm us with misinformation. This was very pertinent during the Covid-19 crisis, where false treatments reached millions. A study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene estimatedthat nearly 6,000 people were hospitalised during the pandemic due to misinformation, from ingesting methanol to relying on unproven herbal remedies.

Furthermore, the rise of social media and a culture of ‘relatability’ has also led to the normalisation of discussing physical and mental health conditions. This has been great for destigmatising health and bringing awareness. On the flip side, it has led to chronic self-diagnosis. With a quick Google search, seemingly normal symptoms can escalate very quickly, fuelling anxiety rather than alleviating it.

Improving diagnosis

But the effects of technology on our healthcare starts long before diagnosis. Behind every pill bottle now lies not just a lab, but perhaps a server farm. Algorithms can process millions of molecular structures in weeks, something that once took human researchers decades.

For example, in 2022 DeepMind’s AlphaFold solved the 50-year-old “protein folding problem”, predicting the 3D shapes of proteins. This breakthrough has already accelerated research into diseases such as malaria and Parkinson’s. Technology has completely changed scientific timeframes.

If data fuels discovery, diagnosis is where digital tools finally make direct contact with us. Beyond the use of technology in scans, chatbots armed with symptom databases can triage patients before they ever meet a doctor.

Diagnosis used to mean sitting anxiously in a waiting room until a doctor spoke the verdict aloud. For us, it may begin in the glow of a phone screen.

There is reassurance in the precision, but also unease for those dealing with an unfamiliar system.

Care itself has crossed the threshold of geography and time. Telemedicine has allowed a consultation to occur from quite literally anywhere. For those raised on FaceTime and video calls, the experience of seeing a doctor on a laptop no longer feels unnatural. It is an efficient and accessible option, especially for those in remote or underserved areas.

Wearable devices can continuously monitor an individual’s heart rate, glucose levels, sleep patterns and more, alerting patients and doctors to potential issues in real time. Remote monitoring programmes for heart failure patients have shown reductions in hospital re-admissions and improvements in patient outcomes.

Personalised medicine takes this further. A study published in The Lancet in 2021 used machine learning models to predict anti-depressant response in patients with major depressive disorder, showing that tailoring treatment based on patient-specific profiles could improve remission rates.